|

Correspondence

between C. S. Lewis

and

Mrs. William L. (Philinda) Krieg

and her son, Laurence

1955 - 1958

with commentary by Laurence Krieg, August, 1972 |

|

Foreword - Laurence

In early 1955, when I was nine years old, I was beset with a great concern:

was I guilty of idolatry? Though I don't remember the details, I must have been

very upset and worried, because my mother was moved to write to C. S. Lewis,

who alone, she felt, would be able to clear up the idolatry problem.

But come now: a nine-year-old worrying about idolatry???

Yes, I really was. I remember that much for sure! Here's how it happened: A

few years earlier, my mother had first started reading C. S. Lewis's Narnia

books to me. As my own ability to read grew during the intervening years, I

started reading them for myself, and the more I read the better I liked them.

In fact, I didn't just like them; I was totally and joyfully absorbed in them,

and certainly found them at least as 'real' as the everyday world. Nothing unusual

about that; but what worried me was that I found Lewis's portrayal of Aslan

much more appealing and worthy of worship than any church or Sunday School's

portrayal of God or Jesus. My parents, with the fervor of those recently converted

from agnosticism (or 'heathenism' as my mother called it) to Christianity, made

sure that I went to Sunday School regularly. I had been thoroughly taught that

one of the worst things a person can do is worship a false god - that is, any

god but God. This was impressed on me at Sunday

School with commendable force and clarity!

Yet there I was: I knew I should 'love the Lord my God with all my heart, and

all my soul, and with all my might' (Deut. 6:4), but I couldn't help loving

Aslan more!

So I got depressed about not being able to wrench my true affections away from

Aslan, and my mother, as I said, wrote directly to C. S. Lewis about it.

I still remember my surprise at the idea that one could write to the author

of a book; but that wasn't nearly as great as my surprise when I came home from

school one day and found that a letter from C. S. Lewis had actually arrived!

The copy of this letter which my mother typed for me is the only copy of the

letter that Lewis actually wrote. In addition to my problems, my mother

had asked Lewis about some of her own, and she did not think I should be advised

of them at the age of nine; besides, Lewis's handwriting was at that time rather

poor, so she made a typed copy of the parts of the original letter which applied

to me. This original, together with a copy of her first letter to Lewis, were

kept separate and have now been misplaced.

Introduction - Philinda

“I sent my first letter to Lewis enclosed in another to his publishers,

Macmillan, in which I told them in no uncertain terms that their author had

made my little boy unhappy and I expected them to do something about it right

away. Having gotten rid of my anger in this epistolatory way. I felt much better

about it and was really very surprised when C. S. Lewis' first letter arrived

only ten days later. Surprised, overwhelmed. delighted, joyful! The moments

while I was deciphering that letter were among the happiest in my life, as if

I'd received a message straight from Heaven. And indeed I think I can tentatively

date my understanding of the work of the Holy Spirit from those moments...

“I do ... remember that on at least one and more probably two occasions

Lewis sent his letter to you [Laurence] with a covering note to me. As I remember

the covering notes were humbly and modestly hoping that 'the letter to Laurence

was all right, and would do the work of reconciliation required.' Only a great

man could show such true humility. ”

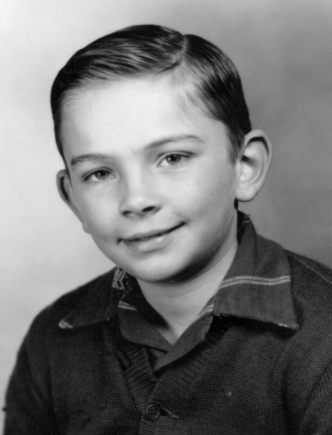

Laura Philinda Campbell Krieg in 1957

Photo: credit Robert Striar News Photo

|

|

C. S. Lewis to Philinda Krieg, 1955-05-06

Magdalene College

Cambridge

6/5/55

Dear Mrs. Krieg,

Tell Laurence from me, with my love:

1/ Even if he was loving Aslan more than Jesus (I'll explain in a moment why

he can't really be doing this) he would not be an idol-worshipper. If he was

an idol worshipper he'd be doing it on purpose, whereas he's now doing it because

he can't help doing it, and trying hard not to do it. But God knows quite well

how hard we find it to love Him more than anyone or anything else, and He won't

be angry with us as long as we are trying. And He will help us.

2/ But Laurence can't really love Aslan more than Jesus, even if he feels that's

what he is doing. For the things he loves Aslan for doing or saying are simply

the things Jesus really did and said. So that when Laurence thinks he is loving

Aslan, he is really loving Jesus: and perhaps loving Him more than he ever did

before. Of course there is one thing Aslan has that Jesus has not - I mean,

the body of a lion. (But .remember, if there are other worlds and they need

to be saved and Christ were to save them - as He would - He may really have

taken all sorts of bodies in them which we don't know about.) Now if Laurence

is bothered because he finds the lion-body seems nicer to him than the man-body,

I don't think he need be bothered at all. God knows all about the way a little

boy's imagination works (He made it, after all) and knows that at a certain

age the idea of talking and friendly animals is very attractive. So I don't

think He minds if Laurence likes the Lion-body. And anyway, Laurence will find

as he grows older, that feeling (liking the lion-body better) will die away

of itself, without his taking any trouble about it. So he needn't bother.

3/ If I were Laurence I'd just say in my prayers something like this: "Dear

God, if the things I've been thinking and feeling about those books are things

You don't like and are bad for me, please take away those feelings and thoughts.

But if they are not bad, then please stop me from worrying about them. And help

me every day to love You more in the way that really matters far more than any

feelings or imaginations, by doing what You want and growing more like You."

That is the sort of thing I think Laurence should say for himself; but it would

be kind and Christian-like if he then added, "And if Mr. Lewis has worried

any other children by his books or done them any harm, then please forgive him

and help him never to do it again."

Will this help? I am terribly sorry to have caused such trouble, and would

take it as a great favor if you would write again and tell me how Laurence goes

on. I shall of course have him daily in my prayers. He must be a corker of a

boy: I hope you are prepared for the possibility he might turn out a saint.

I daresay the saints' mothers have, in some ways, a rough time!

Yours sincerely,

C. S. Lewis

So far, the threat of my turning out a saint (in the narrow sense) has not

come true!

Philinda Krieg to C. S. Lewis, 1955-10-20

5208 Glenwood Road

Bethesda, Maryland

October 20, 1955

Dear Mr. Lewis,

My son Laurence, who is certainly among your most devoted admirers, blows

hot and cold on the matter of my writing to thank you for your blessed letter

of last May. One day he'll say I should write you immediately with profuse

thanks, and the next he'll urge me to hold off, or at least write a very short

note. "If you write a long one, Mr. Lewis will take a long time to read

it, and then he won't finish the next Narnia book quickly."

However, last May he rightly insisted that we answer your kind letter without

delay, and he wanted to do it himself. But he was ashamed of his poor handwriting,

and hopes you will forgive his using me as his typist. It is true that this

was the speediest and clearest way for him to express his personal thanks,

which he was most anxious to do. Fortunately, your handwriting is as illegible

to him as his would be to you, so that by the time he came home from school

on the happy day when your letter arrived, I had been able to make a typed

copy for him to read, with certain omissions. I gave it to him because I knew

he would want to know what were your exact words. I left out only the parts

that were obviously for me. Your arguments satisfied him completely, and we

have had no recurrences of his attack of self-condemnation for idolatry. Since

then, he has re-read all of the first five Narnia books happily, and was overjoyed

the other day when a friend gave him The Magician's

Nephew. This last Narnia book was one we hadn't even heard about. We

were both very excited, and started to read it aloud immediately. "Now

I'll know how the White Witch came to Narnia in the first place!" shouted

Laurence, "And now you must thank Mr. Lewis right away!"

I said I'd write as soon as I could, and actually I'd been hoping to get a

chance to do so for months. What Laurence doesn't realize is that it's a good

fifteen-hour day seven days a week, this business of being wife and mother of

three. Laurence has twin sisters four years old, who are at present earnestly

practicing up for apprentice cowboys. What's more, summer and school-free days

have been upon us for what seems many months. But now it's almost our Thanksgiving

time! I can't think of a better occasion to tell you how very thankful we are

to you.

I'm grateful on my own, as well as Laurence. Of the books written by Mr.

C. S. Lewis and published by Macmillan, I've managed through the years to

get hold of copies of all save That Hideous Strength.

I've bought several copies apiece of Mere Christianity

and Screwtape Letters, so I could leave them

around the house conspicuously, with the hope (well realized) that people

would take them up, get interested, and make off with them. I'm happy to say

I've had great success, for I've lost two Screwtapes

and one Mere Christianity, which may or may

not be returned later. One friend to whom I loaned Screwtape

(she returned it) liked it so much that she took to giving copies away freely

during a transcontinental motor trip this summer, until her husband arbitrarily

decided that five Screwtapes were all the family finances could afford this

year. I'm attached to Screwtape, because it

was the first of your books I read, but nowadays the one I want to have around

at all times is The Problem of Pain. I no longer

leave The Problem around where it can be picked

up handily - I lost my first copy that way several years ago, to a respectable

clergyman in Guatemala who appealed to my better nature. The other two books

are more easily come by. My husband is in the U. S. Foreign Service, and we're

often in out-of-the-way parts of the world where it's hard to buy books and

next to impossible to find them in libraries.

I started out with Wormwood as an ignorant heathen, but he and his uncle

Screwtape frightened me into going through Mere Christianity

to Brunner, Niebuhr, and Tillich, etc. But the clarity of the first two Christian

books I read is as astonishing and illuminating as the first time I read them.

I've found in The Problem of Pain the basis

for an attempt at fortitude which has proved nearly indispensable at several

bad moments in the past few years.

God bless you for it. Since it's impossible to calculate how much I owe you

on my own, as well as for Laurence's joy in Narnia, I can only assure you

that you are thankfully remembered daily in the Krieg family.

Laurence would accuse me of long-windedness right now, quite correctly.

I was only to say thank you very briefly, and then let you continue with the

important job of letting us all know what happened next in Narnia.

Your grateful reader,

[Mrs. William L. Krieg]

P.S. Laurence wants me to tell you that he hopes you'll be charitable toward

panthers. He admires them greatly, as he does lions, their cousins. "They

act pantherish because that's the way God made them, and they are really beautiful."

C. S. Lewis to Laurence Krieg, 1955-10-24

Magdalene College,

Cambridge.

24/10/55

My dear Laurence - I was very glad to get a letter from your Mother to-day

because now I can answer one you wrote me a long time ago. The reason I could

not answer you before was that the corner of your letter got wet before it

reached me and the address was all blotted out so that I could not read it;

so I did not know where to send my answer to.

ow: I don't dislike Panthers at all, I think they are one of the loveliest

animals there are. I don't remember that I have put any bad panthers in the

books (there are some good ones fighting against Rabadash in The

Silver Chair [sic], aren't there?) and even if I have that wouldn't

mean I thought all Panthers bad, any more than I think all men bad because

of Uncle Andrew, or all boys bad because Edmund was once a traitor.

I'm sorry my handwriting is so hard: it was very nice un til about 10 years

ago, but now I have rheumatism in my wrist. Please thank your Mother for her

nice letter: I enjoyed it very much. And now good-bye. Don't forget sometimes

to put in a word for me when you say your prayers, and I'll do the same for

you.

Yours ever

C. S. Lewis

Philinda Krieg to C. S. Lewis, 1956-01-23

5208 Glenwood Road

Bethesda, Maryland

January 23, 1956

Dear Mr. Lewis,

Laurence and I earnestly wanted to send you first our best wishes for Christmas,

then for the New Year, and failing to send the previous two batches of good

wishes, I hoped to make it by Epiphany, at least! Two cases of mumps, two mysterious

viruses, and the feverish preparations for Christmas (which, alack, is more

of a feat than a feast for mothers) delayed me so that the next occasion for

sending you our thanks and greetings would be Easter. I thought I'd better "carpe

the diem", as Laurence says, occasion or no occasion just in case the household

is struck with measles or chicken pox tomorrow.

Laurence was perfectly able to read your kind letter to him, of October 24,

and we were both very sorry to hear that your wrist had been troubling you.

He was pleased by your flattering words about panthers, and took great boyish

glee in the fact that you said some panthers fought against Rabadash in The

Silver Chair: "Rabadash is in The Horse and

his Boy! Mr. Lewis doesn't even know his own books as well as I do!"

So all in all, your letter made Laurence a very happy boy that day. He was

prevented from re-reading the Narnia books for the fourth time, however, by

the pressure of school work. His teacher, a woman of iron determination, has

been insisting on his reading Mark Twain, Louisa M. Alcott, R. L. Stevenson,

Kipling, and the rest before returning to Narnia. She has also been ruthless

about his hand-writing and his 13 times table. I trust that by the time she

finishes scraping and polishing him, Laurence will be competent to write you

a legible letter himself, and perhaps even improve on his mother's spelling.

I have to report to you the loss of a second copy of The

Problem of Pain, due to lack of caution on my part. I carelessly loaned

it to an acquaintance who seemed to have an honest face, but who immediately

skipped off to California leaving behind only a note to the effect that she

hoped I didn't mind if she took The Problem

with her to read it over again. Fearing never to see that copy again, I ordered

a third. This new one says in it, "Eleventh Printing, 1955" a situation

which I'm beginning to consider gloomily to be my own fault.

Now I should like to ask you a question. I've been helping Laurence with his

Sunday School lessons recently, and I'm sorry to say that while they aren't

too easy, they are extremely dull. As you know, my son is genuinely interested

in Christianity, and willing to work at learning about it. So it pains me to

see his very real interest being nearly killed by uninspired lessons. Surely

it would be possible to write a series of lessons more clearly and catchingly!

I had to watch him go forth from the eager, joyful atmosphere of Narnia into

this plodding, anemic Sunday School world. I wished very much that someone would

try his hand at writing solid lessons in Christianity for children, but with

fire and clarity, aiming to catch their imagination and hold their interest.

I've had this in mind ever since I read the last chapter of The Voyage of the

Dawn Treader. Granted that the older children must eventually leave the magic

world of Aslan for their own world of men and women, but where can they find

continued appeal to their hearts and minds? Not in any Sunday School lessons

I've seen. And they aren't quite ready yet for adult reading, devotional or

theological. It would admittedly be a difficult task to combine a clear presentation

of Christianity for older children and adolescents with an attempt to evoke

the same eager, magically wonderful response which Aslan calls forth. But it

should be attempted; children that age can be "caught", too. They

need to be given the opportunity to see visions and mysteries, rather than being

drowned in dully solemn lessons. It's a wonder to me that the Sunday School

graduates can ever feel "the joy of Thy salvation" during the rest

of their lives.

Needless to say, this was less of a question than an appeal. You did such a

splendid job on Mere Christianity for grown-ups, that I should dearly love to

be able to give Laurence and the twins something along the same line suited

to their development. The twins are only four and therefore in their case, I

can wait in patience. Laurence also can continue in Narnia for a couple of years.

But then what?

Laurence and I both send our heart-felt though sadly belated good wishes to

you, and many thanks for your letter.

Sincerely yours,

[Mrs. William L. Krieg]

C. S. Lewis to Philinda Krieg, 1956-01-28

Magdalene College, Cambridge.

28/1/56

Dear Mrs. Krieg

About an hour after posting my last letter to Laurence I realized that I

had attributed to The Silver Chair what really

comes in The Horse. I thought Laurence would enjoy catching me out on my own

books and should have been much disappointed if he had not!

One is sorry the Sunday Schools should be so dull. Yet I wonder. In this

all important subject, as in every other, the youngsters must meet, if not

exactly the dull, at any rate the hard and the dry, sooner or later. The modern

attempt is to keep it as late as possible; but does that do any good? They've

got to cut their teeth. Aren't many parts of the Bible itself, read at home,

quite simple enough and interesting enough to be a counterpoise to the dull

teaching? Anyway, there is no use trying to keep the first thrill. It will

come to life again and again only on one condition: that we turn our backs

on it and get to work and go through all the dullness. But I've said all this

in the P. of P., now I come to think of it.

I don't think any book I could write w[ould] help. You can help; but in the

main there is something at this stage which Laurence can (and without doubt,

he will) do for himself.

Love to both.

Yours sincerely

C. S. Lewis

Of course he must pray to God to keep his interest alive. He knows God is not

really dull. He must still remember that and trust Him even when God doesn't

show him any of the interestingness. He is there alright behind the dull work.

Philinda Krieg to C. S. Lewis, 1956-02-12

5208 Glenwood Road

Bethesda, Maryland

February 12, 1956

Dear Mr. Lewis,

Heavenly days! My last letter to you was so badly expressed and so confusing

that I seem to have given the impression of favoring the coddling of the young,

Progressive Education, easy lessons, and perhaps even higher crimes and misdemeanors.

Far from it. I'm one at heart with Laurence's stern and rockbound teacher, Miss

Wood, and between the two of us we keep the poor boy thoroughly occupied with

his studies. The harder the better. However, I asked Laurence this morning if

he didn't consider his teacher and his mother two of the most ruthless and hard-driving

women alive, only to be disappointed when he replied, "Oh, Miss Wood makes

me work hard, all right, but she's a good teacher. And you're only mildly ruthless,

I'd say." I shall bear that frank appraisal in mind, practice my technique

with the lash, and ignore his groans from now on. Mildly ruthless indeed!

I can only account for my confusing you by the fact that, like Alice and the

Queen, I must keep running to stay in the same place. The twins consider maternal

letter-writing a flagrant attack on their rights, so I must carry on all correspondence

in strictest secrecy while they are asleep, and be ready to hide the evidence

on a moment's notice should I hear signs of stirring from above. At the same

time, I must watch to see that the pie isn't burning in the oven, that Laurence

is studying rather than dreaming, and that the washing machine hasn't finished

its job yet. Jack of all trades is master of none.

As for reading the Bible, Laurence does so. He is far more familiar with

the early history of the Hebrews than I am (since I was a heathen until recently)

and enjoys asking me such embarrassing questions as "How many soldiers

did Gideon have?", or "What was the name of the king in Elijah's

day?". Not only in Sunday School and Summer Bible courses, but also in

school during the week, he acquires ammunition for the joyous salvos. I suspect

the redoubtable Miss Wood of violating the Constitution of the United States

in this matter, but until she is challenged and defeated in this issue, Miss

Wood is having her pupils learn the books of the Bible, the names of the apostles,

and some of the more complicated details of Hebrew history. I can still take

the lead when it comes to the prophetic books (though the lead is narrowing

fast), and I'm way ahead of Laurence on the New Testament. Probably the New

Testament is considered more difficult for the younger children. I believe

they are right to start at

the beginning and work forward. One could not understand the New Testament (other

than intellectually) without a sense of sin. The prophets are a little easier,

but nonetheless they involve concepts and discuss issues which simply haven't

arisen yet on ten-year-old horizons.

What I was complaining about was bad writing in Sunday School lessons. Laurence's

lessons are ill-phrased and spotty. One question will be perfectly simple, the

next will be knotty. For example: question one was: In which kingdom did Isaiah

live? Question two was: Why do you suppose Isaiah's vision in the Temple led

him to cry, "Woe is me, for I am undone"? In a laudable effort to

conserve paper, an inch of blank space was assigned to each question, and in

those spaces the child was supposed to enter his answers. My husband and I spent

half an hour trying to compose an answer short enough to fit in the second space,

and Laurence was hopelessly lost, naturally.

To paraphrase the words of a well-known authority, the lessons sound as if

they had been gotten together by a "bench of bishops", learned and

pious but without experience in the art of writing Sunday School Lessons. Laurence's

Sunday School teacher tells me that he has so much difficulty himself, trying

to figure out the ambiguities that crop up, that he often simply tells the boys

to skip over this or that paragraph.

What I was thinking about was this: Laurence will soon be entering the trying

period of adolescence. The certainties of childhood will be gone, and he'll

find himself in a strange, new world where he'll have to face frightening

problems alone. From my own experience and from what I gather listening to

parents of adolescents, I believe the period from thirteen years to seventeen

or eighteen is quite commonly the loneliest and most agonizing human beings

have to endure. They are cut off by the growth process from their old physical

and emotional environment, and feel unprepared to cope with the new. Yet in

the natural course of events, they tend to break away of themselves from all

their childhood patterns, to step aside in order to reexamine everything they

were ever told by parents and teachers. I've been told by many unhappy mothers

that John and Susan will no longer listen to a word of advice, no longer confide

in their father or mother, and are in a general state of rebellion. But I

also remember from my own youth how it seemed that an impenetrable glass wall

had sprung up overnight between me and my father, how I yearned to be able

to confide my troubles and perplexities but was somehow unable to, and how

glad I would have been if I could have found some guide, some map to show

the way I might get out of the maze and onto the right road to full adulthood.

I believe that for two or three years, this guidance comes best from outside

the family. I used to swallow whole almost anything I read in print, but was

very critical of my good father's opinions. Apparently this reaction is well-nigh

universal, so I trust William and I won't be surprised and hurt when a gawky,

man-sized stranger named Laurence looks at us with newly critical eyes. At

this point, I should like to be able to hide a good map or guide book somewhere

so that the suspicious and sensitive stranger can discover it himself. I would

hope the guide book managed to present the issues which young people must

face in clear, unambiguous form; that it did not patronize or talk down or

make the least hint of fun of serious-minded and earnest youths. Also, I'd

hope the author had borne in mind that he was dealing with people intellectually

able and willing to study hard problems, understand difficult concepts, tackle

the toughest philosophy, - but hampered by lack of experience; intelligent

immigrants to a new world. I'd like the book to represent Christianity, almost

as if the young immigrants had never heard of it before, since undoubtedly

they'll have to re-examine that along with everything else. I'd especially

like a discussion of the Christian virtues, and how adult Christians ought

to behave. As I remember, I felt at that age perfectly bewildered by the multiplicity

of paths in front of me and the lack of signposts. After taking a wrong turning

and going back, I'd often see a sign I hadn't seen before. "How could

a great, big grown up girl like you fail to notice such an obvious sign?"

It's hard for mature people to remember how difficult those signs are to decode

at first, and how much tactful guidance is needed but not asked for. I doubt

whether the best intentioned "bench of bishops" could write such

a book.

Please pardon my long-windedness. Laurence doesn't say so, but I can read

in his face that he'd like me to send you his adoring love.

May God bless and keep you,

[Mrs. William L. Krieg]

C. S. Lewis to Philinda Krieg

Magdalene College

Cambridge

16/2/56

Dear Mrs. Krieg

You and Miss Wood seem to have the right ideas! I shouldn't even be surprised

if the children themselves saw no more difficulty in the second question about

Isaiah than in the first. Probably they wrote down "Because he was a man

of unclean lips etc". After all, that is why he said he was undone. (v.[ery]

likely some of them, having been scolded for not washing their teeth, think

Isaiah was repenting the same sin? Which, in its simple ritualism, may be closer

to certain aspects of O.T. conscience than all the comments of "a bench

of bishops").

What to do about adolescence, I've no idea: except a recurrent bachelor's

wonder how anyone has the nerve to produce and bring up a child at all - yet

quite ordinary people seem to do it quite well. Perhaps the uneducated do

it best v.[ery] often. I suppose they don't attempt to replace Providence

or to be Destiny, but just carry on from day to day on ordinary principles

of affection, justice, veracity, and humour. By the way, my Xian Behaviour,

if suited for anyone (of which I'm no judge) is quite as suited for 16 year-olds

as for anyone else. Of course one does at that age believe anyone rather than

one's parents. The hard thing is that (after childhood) parents seem usually

to be most appreciated when they're dead. I find so many turns of expression

etc. of my father's etc. coming out in me and like it now - I'd have fought

against it as long as he was alive.

Give my love to Laurence,

Yours most sincerely

C. S. Lewis

Philinda Krieg to C. S. Lewis, 1956-04-21

In mid-April, 1956, we received a parcel in the mail from England, addressed

in Lewis's most careful hand and stamped with multi-colored likenesses of Elizabeth

II. This proved to contain an autographed copy of The Last Battle. Here are

the thank-you notes it evoked:

5208 Glenwood Road

Bethesda, Maryland

April 21, 1956

Dear Mr. Lewis,

Your virtue in sending Laurence an early copy of The

Last Battle must be its own reward, since you did the act of kindness

in full awareness that it would only provoke a thank-you letter to swell the

tide of mail awaiting you some morning. When I read in Surprised

By Joy that the morning mail is a thing you must steel yourself to

bear, coals of fire began burning my head. I would spare you even this addition

to the day's post if I were not bursting over with gratitude - and at least

thank-you letters aren't the sort that have to be answered!

The book arrived at a most strategic moment, just as the three children and

I, too, were recovering from chicken pox. In these days of inflated prices,

chicken pox is a real bargain in hair shirts. Not only does it provide natural

mortification of the flesh at low cost, it also gives one's friends a good

laugh while preventing its victims from falling into pride of suffering. Since

I was afflicted with twice as many pox per square inch as any of the children,

I was a most sympathetic nurse to them. The arrival of The

Last Battle brightened our pock-marked gloom.

This is a double-barreled thank-you letter (see, I'm doing my best to reduce

the volume of your mail) because I also want to thank you on behalf of a friend.

I sent her a copy of The Problem of Pain

a few months ago, after much hesitation. The Problem helped me when I first

contemplated tragedy, - but my friend is not contemplating tragedy, she is

living it. Her name is Betty Jane Peurifoy, and we met when my husband was

Ambassador Jack Peurifoy's deputy in Guatemala. They had two sons, Clint and

Danny. Danny was just Laurence's age, so the two boys played and went to school

together, and Danny used to have his lunches and suppers with us a good deal.

To make sure they were eating properly, I used to read aloud to them, sometimes

from the Narnia books. Jack Peurifoy was transferred as Ambassador to Thailand

at the same time my husband was transferred to Washington, late in 1954. The

Peurifoy family had been in Thailand less than a year when Jack and Danny

were killed in a road accident, and their other son nearly killed. Clint survived

only because he has cerebral palsy and was unable to tense his muscles the

moment before the crash.

Mrs. Peurifoy is as courageous as she is beautiful, but to bear such a blow

must call for more continuous courage than most heroes require. She is devoting

her life to caring for Clint, who couldn't walk without help before the accident

and is now recovering from a series of bone-graft operations on his legs.

When I sent Betty Jane The Problem I wondered

if I weren't doing the equivalent of sending my grandmother a treatise on

sucking eggs. So I was relieved when she wrote from her home in Oklahoma saying

that she was re-reading the book, and kept it on her night-table. She came

for a short visit to Washington last week, and called me by telephone to say

she had brought The Problem with her in her

suitcase along with other daily necessities. "It's a kind of Bible for

me," she said.

I hope this will serve to encourage you to write more books, as it has encouraged

me to give more of your books to my friends.

Laurence is sending you his picture, because we now have your picture at last

- on the back of the dust jacket of Surprised by Joy.

Gratefully,

[Mrs. William L. Krieg]

Laurence Krieg to C. S. Lewis, 1956-04-12

Dear Mr. Lewis,

This letter is to thank you for sending The Last

Battle, which I like so much that I am thanking you for it at the beginning

of this letter. For I usually give thanks at the end of letters.

The part that I think shows facts of life best, is the part when the children

wondered what would happen if they were killed in Narnia, but thought it would

be better to die there than in a dull way in their own world. Whether they

knew the Apostles' Creed or not, I don't know, But if they did, they must

not have been thinking about it. But as our pastor says, it's hard for people

to keep believing in life after death. When pastor talked about the Apostles'

Creed, I only believed the part about life after death for a short time. But

since I read The Last Battle I believe it

all the time.

My mother told me that some people say when you're in heaven you just sit around

playing the harp, but I think that Narnian heaven is much better than that.

If I were in heaven I'd like to go and see things, not just be able to see things.

Though it is my favorite book and I would like to talk about it much more,

I want to make sure that you know you are my favorite author. I'm not just being

polite.

Love,

[Laurence]

C. S. Lewis to Laurence Krieg, 1956-04-27

Magdalene College

Cambridge

27/4/56

Dear Laurence

Thanks for your nice letter and the photograph. I am so glad you like The

Last Battle. As to whether they knew their Creed, I suppose Professor

Kirke and the Lady Polly and the Pevensies did, but probably Eustace and Pole,

who had been brought up at that rotten school did not.

Your mother tells me you have all been having chicken pox. I had it long after

I was grown up and it's much worse if you are a man for of course you can't

shave with the spots on your face. So I grew a beard and though my hair is black

the beard was half yellow and half red! You should have seen me.

Yes, people do find it hard to keep on feeling as if you believed in the next

life: but then it is just as hard to keep on feeling as if you believed you

were going to be nothing after death. I know this because in the old days before

I was a Christian I used to try.

Last night a young thrush flew into my sitting room and spent the whole night

there. I didn't know what to do, but in the morning one of the college servants

very cleverly caught it and put it out without hurting it. Its mother was waiting

for it outside and was very glad to meet it again. (By the way, I always forget

which birds you have in America. Have you thrushes? They have lovely songs and

speckled chests).

Good-bye for the present and love to you all,

Yours sincerely

C. S. Lewis

C. S. Lewis to Laurence Krieg, 1957-04-22

Having read in Surprised by Joy that Lewis was tormented by large

quantities of mail which he dreaded answering, my mother refrained from writing

to him for about a year. Her next letter, of which a copy is not available,

was prompted (in part) by an on-going debate between herself and me: in what

order were the Narnia books to be read? Her contention was that they should

be read in the order in which they were published; she speculated that Lewis

had them ordered that way so that readers could gain an acquaintance with Narnia

first as it was at its prime, in the Golden Age when Peter was High King at

Cair Paravel. Other stories about Narnia were written to explain how Narnia

began and ended, and to show some other interesting periods of its history.

"You can't understand an acorn without seeing an oak," she would say.

My suggested order of reading was in the chronological order of Narnian time:

The Magician's Nephew; The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe;

The Horse and his Boy; Prince Caspian; The Voyage of the

Dawn Treader; The Silver Chair; and The Last Battle.

Here is Lewis's response:

The Kilns, Headington Quarry

Oxford, England

April 22d 57

Dear Laurence

I think I agree with your order for reading the books more

than with your mother's. The series was not planned beforehand as she thinks.

When I wrote The Lion I did not know I was

going to write any more. Then I wrote P. Caspian

as a sequel and still didn't think there would be any more, and when I had

done The Voyage I felt quite sure it would be

the last. But I found I was wrong. So perhaps it does not matter very much

in which order anyone reads them. I'm not even sure that all the others were

written in the same order in which they were published. I never keep notes

of that sort of thing and never remember dates.

Well, I can't say I have had a happy Easter, for I have

lately got married and my wife is very, very ill. I am sure Aslan knows best

and whether He leaves her with me or takes her to His own country, He will

do what is right. But of course it makes me very sad. I am sure you and your

mother will pray for us.

All good wishes to you both.

Yours

C. S. Lewis

C. S. Lewis to Laurence Krieg, 1957-12-23

It happens that my parents have a large and comprehensive Christmas card list,

and although they knew Lewis did not "believe in" Christmas cards

they sent him one for the next two years. Copies of what was written on these

cards were, of course, not kept, but both of them were accompanied by brief

notes about our family's doings. Lewis bravely responded to them with short

letters.

Magdalene College

Cambridge

Dec 23d 1957

Dear Laurence

It is lovely to hear that you still enjoy the Narnia stories. I hope you are

all well. I forget how much of my news you and your mother know. It is wonderful.

Last year I married, at her bedside in hospital, a woman who seemed to be dying:

so you can imagine it was a sad wedding. But Aslan has done great things for

us and she is now walking about again, showing the doctors how wrong they were,

and making me very happy. I was also ill myself but am now better. Good wishes

to you all.

Yours

C. S. Lewis

C. S. Lewis to Philinda Krieg, 1958-12-22

The Kilns,

Headington Quarry,

Oxford

Dec 22d 1958

Dear Mrs. Krieg

Thank you for your kind card. I am very sorry to hear of Philinda's trouble.

Laurence has long been in my prayers and I will of course mention her too. I

wonder how much Laurence is changed. I expect there are wonderful things to

be seen in Chile. I'd never want to go to a place for the sake of its climate

(not being a vegetable!) but landscapes, birds, beasts, smells, foods, wines,

and people are another matter.

We are both well. With me it has been recovery: with my wife it has been more

like resurrection.

With all blessings.

Yours sincerely

C. S. Lewis

The mention of Chile was in response to the news that the Krieg family was

now living there; my father was assigned at that time to Santiago.

The "trouble" referred to in the second reply was diagnosed as labyrinthitis,

an infection of the canals in the head which are connected with those of the

inner ear and affect balance. The result of this affliction (which was practically

impossible to treat) was a loss of the ability to read - doing so produced extreme

dizziness and nausea. This condition made it nearly impossible for my mother to continue

doing the sorts of things she liked to do, including carrying on a correspondence

with Lewis. The labyrinthitis and its complications did not clear up until after

Lewis's death in 1963.

C. S. Lewis to Philinda Krieg, 1960-11-21

60/500

The Kilns, Kiln Lane,

Headington Quarry,

Oxford.

2Ist November I960

Dear Mrs Krieg,

Naturally it is very pleasant to me to hear that you all enjoy my Narnian books, and it was good of you to take the trouble to let me know. You are more fortunate than I am; my loaned books very rarely come back to me!

With all good wishes,

yours sincerely,

P.S. Laurence Krieg? It can’t be the Laurence Krieg whose mother wrote to me and to whom I wrote years ago? He couldn’t have grown up and founded a family in the time. But the recurrence of both names is staggering.

This letter is typed on a half-sheet of paper, using a blue ink-ribbon. It appears to have been a small machine without the number "1" or exclamation mark. Note the use of capital "I" for the number "1" in the date, and (in the original) the exclamation mark filled in with a small pen-stroke. Biographies of Lews mention that his brother, Major (retired) Warren "Warnie" Lewis, was in residence at The Kilns in 1960, and used to help his brother with correspondence. The number in the upper left corner was probably a file-number (perhaps indicating the 500th letter of 1960?) used by Major Lewis, satisfying his sense of military good-order.

Instead of a signature, a note in Lewis's handwriting expresses a recognition of the name Laurence Krieg, without apparently recollecting the substance of the previous letters. This is not too surprising, since two very stressful years had passed without correspondence between us. During that time, his wife Joy had died, and Lewis had written A Grief Observed (published 1961) chronicling the depth of his sorrow.

It's interesting to note that this brief letter was dated three years and one day before Lewis's death, November 22, 1963.